Overview

The Lasting Special Places Sub-goal: Protected Areas and their Environmental Impacts

Fri, Sep 15, 2023

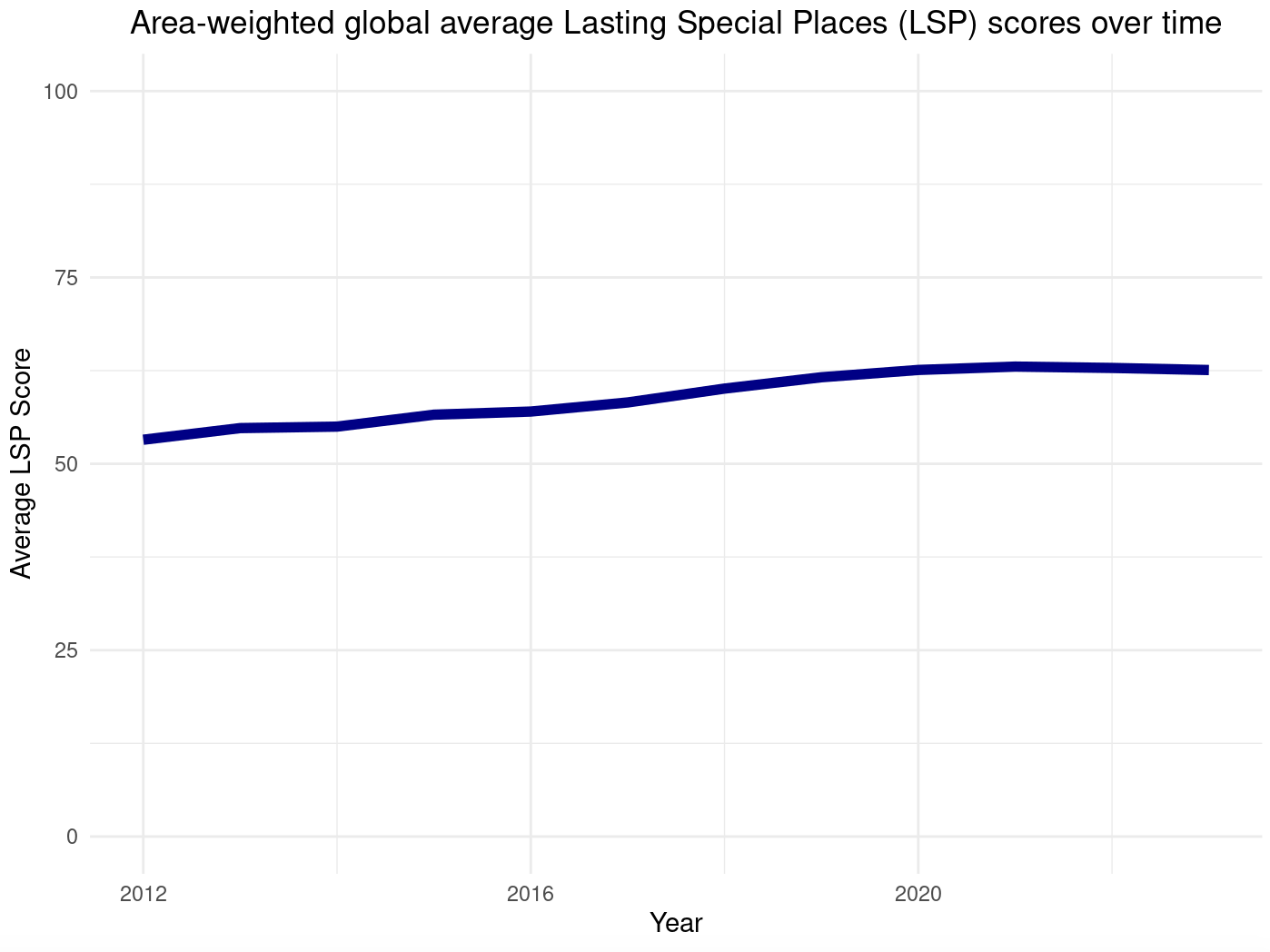

The Ocean Health Index’s (OHI) Lasting Special Places (LSP) sub-goal within the Sense of Place goal aims to quantify “how well we are protecting the locations that contribute to marine-related cultural identity” (OHI, n.d., para. 1). We look at that in terms of meeting a threshold of protection: 30% of coastal area protected for a given OHI region translates to a score of 100 for this sub-goal, with coastal area defined as the combined area 3 nautical miles (nm) offshore and 1 kilometer (km) inland along the OHI region’s coast. This means that “protected areas” are an integral part in calculating the scores for the LSP goal. The LSP sub-goal stands out in the OHI assessment because it is the one of the only scores that has almost exclusively increased over the years (as protected areas typically are not lost). The graph below depicts the change in the area-weighted average global LSP score over time.

This means that we are continuing to approach the global movement’s goal of having at least 30% of oceans and 30% of land protected by 2030, supporting environmental health and sustainability (Einhorn, 2022). While this is positive news, people may be left wondering: what exactly counts as “protected areas"? How effective are these “protected areas” at creating environmental benefits?

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) considers a “protected area” a “clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” (IUCN Definition, 2008, as cited in IUCN, n.d., under heading “What are effective protected areas”). This can include “national parks, wilderness areas, community conserved areas, nature reserves and so on” (IUCN, n.d., under heading “About effective protected areas”). Marine protected areas (MPAs), specifically, can include sites such as “marine parks, marine conservation zones, marine reserves, marine sanctuaries, and no-take zones” (National Geographic, n.d., para. 3).

Protected areas in general have been considered to assist with global biodiversity retention, but how much they protect from local extinctions in their current state is unclear (Williams et al., 2022). They are often not big enough, lack enough suitable habitat, and/or lack proper connections to provide resilience for various species.

MPAs can lead to increases in marine biomass, greater resilience in response to environmental change, and increases in fish abundance, which can also assist areas external to the MPA (Grorud-Colvert & Lubchenco, 2017). MPAs demonstrate these benefits most when they are large, are older, have strong enforcement, are isolated by depth of water or sand, and prevent extractive activities (Edgar et al., 2014). They have different levels of protection: fully protected areas prevent all extractive activities, strongly protected areas prevent commercial extractive activities and allow only some recreational extractive activities, and partially protected areas (the most common level of protection) are increasingly more lenient (Grorud-Colvert & Lubchenco, 2017). Partially protected areas are much less likely to show benefits to the degree of fully or strongly protected areas.

Further, MPAs often cause fishing effort to move from the protected area to other areas or result in the increased use of terrestrial environments for food production (often with higher ecological impacts) (Hilborn, 2017). It has been claimed that “MPAs only protect the ocean from legal, regulated fishing,” that they most benefit areas experiencing high fishing pressure, and that other forms of fisheries management should be used before MPAs when possible (Hilborn, 2017, p. 1161). The measurement of the effectiveness of MPAs also relies on evaluation; however, “adaptive management studies that incorporate monitoring data, let alone adequate data on the appropriate time scales for ascertaining responses to management, are lacking” (Nickols et al., 2019, p. 2383). Overall, MPAs often do not have the proper levels and kinds of protection and management to provide environmental benefits to the most useful extent.

While reaching the global protection goal of marine areas would be beneficial, how beneficial it is depends on how we implement MPAs and other protected areas and on what other strategies are used in combination with these, not just the total area protected. To put things in perspective, 7.2% of the global ocean is designated as MPA zones, but only 2.9% is known to be highly or fully protected, so, despite seeing increases in protected areas over time, there is still improvement to be had to both meet the 30% goal and have the level of protection needed for the most beneficial impacts (Marine Protection Atlas, n.d., under heading “Global marine fishing protection”).

References

-

Edgar, G. J., Stuart-Smith, R. D., Willis, T. J., Kininmonth, S., Baker, S. C., Banks, S., Barrett, N. S., Becerro, M. A., Bernard, A. T. F., Berkhout, J., Buxton, C. D., Campbell, S. J., Cooper, A. T., Davey, M., Edgar, S. C., Försterra, G., Galván, D. E., Irigoyen, A. J., Kushner, D. J., & Moura, R. (2014). Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature, 506(7487), 216–220.

-

Einhorn, C. (2022, December 20). Nearly Every Country Signs On to a Sweeping Deal to Protect Nature. The New York Times.

-

Grorud-Colvert, K., & Lubchenco, J. (2017, January 4). Momentum grows for ocean preserves. How well do they work?. The Conversation.

-

Hilborn, R. (2017). Are MPAs effective?. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 75(3), 1160–1162.

-

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (n.d.). Effective protected areas. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

-

Marine Protection Atlas. (n.d.). The Marine Protection Atlas. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

-

National Geographic. (n.d.). The Importance of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Retrieved September 8, 2023.

-

Nickols, K. J., White, J. W., Malone, D., Carr, M. H., Starr, R. M., Baskett, M. L., Hastings, A., & Botsford, L. W. (2019). Setting ecological expectations for adaptive management of marine protected areas. Journal of Applied Ecology, 56(10), 2376–2385.

-

Ocean Health Index (OHI). (n.d.). Sub-Goal: Lasting Special Places. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

-

Williams, D. R., Rondinini, C., & Tilman, D. (2022). Global protected areas seem insufficient to safeguard half of the world’s mammals from human-induced extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(24).

Code for the visualization in this blog post can be found in the website GitHub repository.

This post was created by the 2023 OHI Fellows.