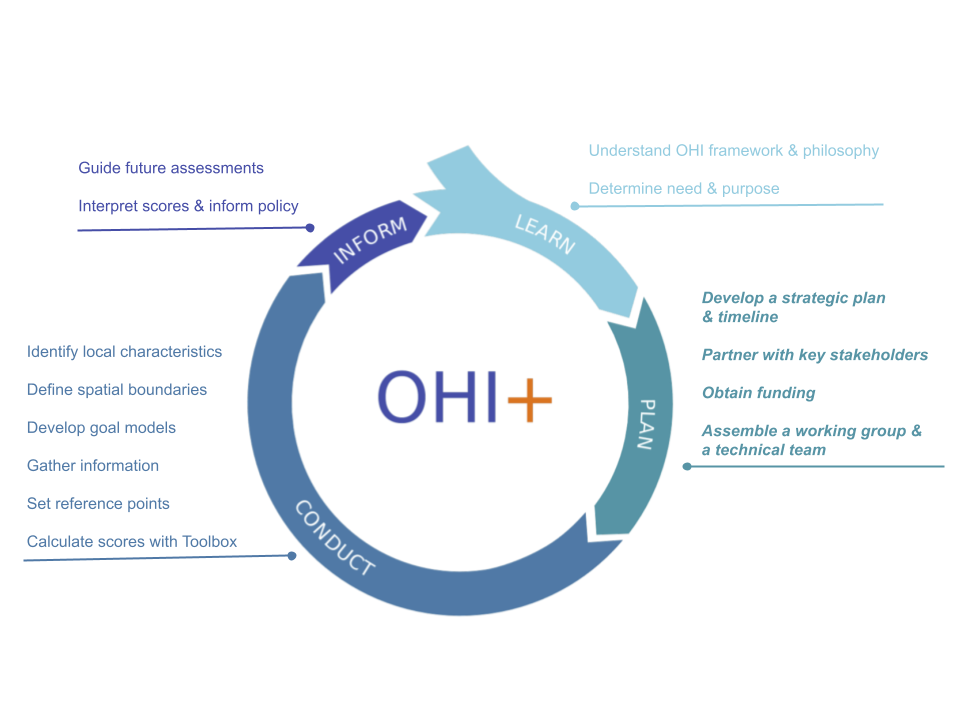

You have successfully Learned about OHI, and you can start Planning your own assessment. This section will help you understand the financial requirements, human resources, and data requirements of conducting an assessment, as well as how to engage stakeholders and assessmble a technical team, in order to Conduct an OHI assessment in the next phase.

Citation: Ocean Health Index. 2016. Ocean Health Index Assessment - Plan Phases. National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, University of California, Santa Barbara. Available at: ohi-science.org/plan

Citation: Ocean Health Index. 2016. Ocean Health Index Assessment - Plan Phases. National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, University of California, Santa Barbara. Available at: ohi-science.org/plan

Download PDF version: https://github.com/OHI-Science/ohi-science.github.io/raw/dev/assets/downloads/other/ohi-plan.pdf*

1 Requirements for Conducting an OHI+ Assessment

Before you begin actually conducting your assessment (explained in Phase 3), it is crucial to have a full understanding of what are required to complete a successful assessment. Conducting an assessment is a labor intensive process that requires collaboration, communication, funding, dedication and data. It is imperative to ensure that you have all of these components before starting your assessment.

There are several key components to effectively prepare for your assessment: - Implement a stakeholder engagement process - Coordinate the assembling of a Working Group and a Technical Team - Collaborative target setting and indicator framework (datasets) - Organize workshops - Develop a strategy and project proposal

Procuring funding and creating a budget that is informed by the task timeline will also aid in smart spending and decrease the likelihood that funding will run out before the process is completed.

Index scores are a reflection of data quality, and thus, accessing the best data available is of the highest importance. Data from existing environmental, social, and economic indicators may be used. All data will be rescaled to specific reference points (targets) before being combined therefore setting these reference points at the appropriate scale is a fundamental component of any assessment. This requires the interpretation of the philosophy of each Index goal and sub-goal using the best available data and indicators. For your reference, you may look at a list of the data layers used in the 2014 Global Assessment for Ecuador at http://ohi-science.org/ecu/layers/

2 Stakeholder Engagement Process

Effective ocean and coastal management is inherently a participatory endeavor. Yet, it is often the case stakeholders with varying interests do not work together, leading to inefficient and unsustainable use of ocean resources. This stakeholder process merges state of the art marine science with the Consensus Building Institute’s (CBI) multi-stakeholder and multi-issue negotiation approach, aiming at embedding scientific research within a functional institutional arrangement adequate for making decisions with the resulting information. This approach can be effectively applied across a range of disciplines and for a wide array of purposes, but in this instance we are applying it specifically for the effective implementation of the Ocean Health Index as a management approach at various scales.

As mentioned in the previous section, the OHI+ process has four main phases, two of which are highly contingent on stakeholder participation: Phase II: Plan, and Phase IV: Inform. Below you can find a detailed outline of the steps involved in each phase of the stakeholder process.

I. LEARN: Understand the OHI framework and its potential applications

II. PLAN: Engage stakeholders to develop an action plan for conducting an OHI+ - Identify the convener - Stakeholder Needs Analysis - Collaborative target setting and Indicator Framework - OHI Workshop

III. CONDUCT: Analyze information (develop models, use OHI Toolbox), identify spatial and thematic priorities

IV. INFORM: Stakeholders and Decision-makers work together to analyze findings and reach agreements based on the information - Test management options (scenarios) - Reach management and policy agreements between stakeholders - Implement agreements on pre-established timelines - Reassess: establish new relevant targets and gather new information

In this section we describe the elements of the ‘Plan’ phase, which happens previous to the scientific assessment, and in section IV we will describe the components of the ‘Inform’ phase, which takes place after the assessment. Keep in mind that this approach is flexible and should be customized to fit the needs and conditions of the study area. You may also contact OHI practitioners in other countries (which you can find in the Projects page) for advice and guidance.

2.1 Identify the convener

The first step in managing towards healthy oceans is to bring stakeholders together by a convener. The convener invites and convenes key stakeholders, facilitates discussions, provides legitimacy to the process, and establishes linkages with ocean managers and decision-makers. In the field of ocean management, government agencies and public interest organizations often become the de facto convener due to their connections with many stakeholders, but it is possible for an individual or even a group of people with other ocean related associations to become effective conveners. An independent organization such as an NGO can help assessing potential conveners taking into consideration the convener criteria. The convener identification process should take into consideration the willingness of the convener to take on the roles and responsibilities for leading the OHI+ process. A successful convener should commit to:

Establishing a collaborative virtual platform for recording decisions and gathering information. Many OHI groups have used Google Drive folders to store all relevant information in the first 2 phases of the process (recommended but not mandatory);

Conduct stakeholder mapping to identify key actors to involve in the process;

Conduct a stakeholder needs analysis (or engage an independent analyst) to understand the concerns and issues affecting stakeholders, and gather information about targets/mandates and data;

Host several workshops to build capacity about the OHI framework, customize the framework to local needs, discuss reference points (management targets), data availability, and other parameters;

Develop a strategic plan for the OHI+ assessment, identifying resources needed, assembling a technical team, and determining a program timeline;

Ensure the proper execution of the OHI assessment;

Work with stakeholders to identify proposed management actions that can be tested within the OHI Toolbox;

Seek agreements with stakeholders and oversee the implementation of those stakeholders.

2.2 Stakeholder Needs Analysis (SNA)

“The Index offers a tool to engage stakeholders and decision-makers in difficult but necessary discussions, while also helping agencies fulfill their mandates” (Halpern et al. 2014)

For your assessment, appropriate conditions and resources will include scientific capacity, government actions (policies, barriers to action, regulatory frameworks and transparency), and civil engagement, all of which create an environment conducive to effectively conducting the assessment.

Although the Index assessments can be produced without the input of non-scientific groups (policy, civil society, etc.), multi-stakeholder collaborative planning and decision-making are more likely to yield integrated management efforts focusing on coordinating multi-sector activities, assessing cumulative impacts and trade-offs, and maximizing sustainable productivity. Therefore, the steps we present here propose establishing a strong multi-disciplinary management and leadership framework, and focus on developing a strong strategic plan that can guide the entire process.

Achieving healthy oceans (i.e., reaching the targets established) will require using information produced from the assessment to adopt management actions and enact policies that gradually improve ocean conditions across multiple ocean goals.

Successful assessments require leadership to help set targets and get buy-ins from various interested parties. The assessment should be an element of a larger strategy to improve ocean health and in no case should it be the sole strategy for improving ocean health.

Once the convener has been identified and it has agreed to take on the role, we recommend the convener conducts or commissions a stakeholder needs analysis to determine whether or not to proceed with the OHI+ assessment. This analysis will also help understand the stakeholders involved; that is, the organizations or groups operating at various management levels (national, sub-national, regional, international, private and public), which have an interest in the management of ocean and coastal resources, and can influence or be influenced by decisions in the way these resources are managed. The SNA also builds trust among stakeholders and helps in the design process for developing and OHI+ since it can also be used to gather information and data. The OHI+ process generally includes four main stakeholder groups: civil society groups (resource users, community groups, NGOs), government agencies (national and local), research and academic institutions, and private sector operators. Given the broad range of these stakeholders, the analysis can help highlight the interests and concerns of various parties, helping to build trust among groups that may have low trust among each other.

The SNA process systematically lists and analyzes information to determine which groups have an interest in OHI+, which groups are typically included or excluded, whether each group is relevant to include, whether the groups support or oppose the initiative, and the concerns from various groups. This process seeks to understand players, their issues and management needs, their core interest in ocean and coastal resources, the potential benefits the OHI process can yield to them. Further, the SNA will also help the conveners understand the linkages between the OHI+ process and management actions, governance capacity, policy changes, resource allocation, etc.

The SNA allows you to:

Determine ocean and coastal management needs;

Identify groups with an interest in those needs;

Learn the concerns and interests of the stakeholders, and assess their incentives and capacities, identify areas of potential agreement and conflict among the stakeholders;

Build trust and for helping to design a process that maximizes the likelihood of reaching a broad consensus on the most important issues at stake;

Include various stakeholder needs and mandates in the assessment

Because OHI+ assessments are participatory multi-stakeholder processes, it is important to carry out the stakeholder analysis and engagement before and throughout the implementation of OHI+. This ensures the assessment aligns with the interests and management needs of various stakeholder needs, and the results will more accurately reflect the true condition of the socio-ecological systems evaluated. The SNA is also a create way to facilitate alliance building and to foresee and prevent possible conflicts. The OHI+ process is more likely to successfully inform decision-making if effective stakeholder analysis is done on an ongoing basis. This is because once scores are produced, stakeholders will have to test management scenarios to identify priority actions, reach policy and intervention agreements, and implement those agreements.

2.2.1 Identify stakeholders and their influence

Initial stakeholder identification consists of listing groups known to influence ocean resource management or be impacted by the OHI+ process. This process provides a basis from which to expand the amount of known stakeholders to the convener as well as begin to analyze those listed. It is important not to rely solely on information or knowledge held by the convener, as this might inadvertently exclude groups that can provide important information or contribute with resources and capacity.

At the outset, list all actors with a potential interest in the project without limiting the list based on whether you know the group will have a stake in the project or not. Later, during analysis and stakeholder engagement, you will have the chance to confirm whether groups have a relevant stake or not. Stakeholders can be identified based on the following categories: civil society and local NGOs, government entities, academic and scientific institutions, the private sector, donors, international NGOs, local leaders or influencers, and others.

Participant stakeholders could include, but are not limited to, the following:

Scientific/Academic institutions:

University research centers

Independent or government scientific institutions and consulting firms

Government statistics departments

Government:

Ministry/Department/Agencies:

Environment

Production

Planning

Fisheries/aquaculture

Tourism

Finance

Health

Technical secretariats

Maritime institutions

Ocean commission

Water quality

Environmental protection

Non-Governmental Organizations, Civil Society, Private Sector, Resource Users:

Coastal community leaders/associations

Indigenous communities

Commercial and artisanal fishing associations

Mariculture producers

Resource extractors (traders, etc.)

Coastal developers

Tourism associations

Environmental conservation and social non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

Ocean dependent industries (mariculture, ports, energy)

Chamber of commerce

You should be able to identify identify:

- The stakeholders to interview

- List of stakeholder to be interviewed

- Managers with mandates and key influencers

- Resource users - those to be impacted by/subjects of actions

- Those with information and sources of knowledge (information management/experts)

2.2.2 Gather information: questionnaires, interviews, focus groups

You may use stakeholder interviews, meetings, and surveys as some of the techniques in the SNA process. It is important to note that conveners may not be perceived as impartial to the process, and thus it may be difficult for them to obtain complete and honest responses from some stakeholders. For this reason, the convener may choose to commission the SNA to an expert independent analyst, but this decision will largely depend on the context, conflict levels among stakeholders, and budgetary constraints. To obtain the most information possible, we recommend using semi-structured interviews using a written protocol and conducting a survey.

2.2.3 Technical team identification

Even though OHI is a participatory assessment, it requires expert knowledge on subjects such as ecology, economics, sociology, biology, policy, programming, GIS. The SNA process should also serve as an approach to identify experts interested in providing technical support for the development of OHI+, as this requires intimate knowledge of local features and resources. There is no required team structure or format, and rather than a specific number of people what is required are specific skillsets. OHI technical teams have ranged from 2 people to 12, although in most cases it ranges from 4-6 individuals working part-time, or fewer individuals working full time.

2.2.4 Stakeholder Needs Analysis report

The SNA process should result in a written report to be shared with stakeholders and those who were interviewed and be widely discussed through multi-party meetings and/or workshops. This report should include, but is not limited to:

Report purpose and overview

Description of the assessment process

Identification of stakeholders, and stakeholder influence and support for the Ocean Health Index process

Interests and needs of various stakeholder groups

Concerns and issues affecting various stakeholder groups. Challenges and opportunities

Existing ocean planning and management processes

Summary of relevant information for each OHI goal: data, targets, etc.

Potential barriers to the development of the OHI+ assessment

Potential contributions by different stakeholders

Potential members for the Technical Team

A proposition of next steps

3 Team Structure

The Team Structure will largely depend on the goal of conducting an assessment, thus there is no single “right” team requirements for developing an OHI+ assessment. Academic-led assessments (such as those led by research labs or for a Ph.D thesis) tend to have fewer people involved. However, most assessments to date have management and/or policy goals, and therefore, have wider stakeholder involvement. Effective assessments are carefully planned and require adequate project leadership and vision. Due to the multidisciplinary nature of the Index, assessments often count with participation of various stakeholder groups. Nevertheless, we recommend a key agency or group assumes the leadership of the assessment to ensure proper planning, development, and engagement throughout the assessment.

However, many successful teams have structured themselves as follows:

1. A Multidisciplinary Working Group

The OHI+ working group for your study area should include government agencies, scientific and academic experts, civil society (resource users), NGOs (social, environmental), and private sectors. By assembling a multidisciplinary working group, you ensure the tasks are evenly divided among the participants, as well as counting with a pluralistic system to include various values and perspectives. This working group is responsible for:

doing the early learning about OHI and developing the Work Plan in Phase 2. provides important guidance to the technical team in terms of stakeholder engagement, goal weighing, reference points, and ensuring the study is aligning with management and policy needs. actively engages with key stakeholders and decision-makers through the process and after assessments are conducted to develop action plans that integrate the findings of the study into management and policy interventions.

2. A Technical Team

The success of your OHI+ assessment process will depend on the effectiveness of your technical team. While every assessment will be done differently–it is always done according to local needs, resources, and priorities–we can provide guidance on the skills required within your team and how other assessments have structured their teams. Team sizes have ranged from two to ten people depending on the scope of the study and the qualifications/skills of the team, particularly the technical members. Whether members work full-time or part-time will also affect the time required to completed the assessment.

It is best to assemble a small core team of skilled, flexible people. Because OHI assessments combine knowledge from multiple disciplines, require developing models and setting reference points, and use innovative, evolving open-source tools, team members will likely be required to work outside of their direct expertise and technical ability and must feel comfortable and have the authority to do so. One approach that has worked well has been to assemble:

A core team that is very knowledgeable about the OHI framework and process, with specific members having backgrounds in marine science and tasked with information gathering and communication or with information processing and the Toolbox (or better yet, a combination of the two).

‘Goal keepers’ that are experts in specific OHI goals to help develop the best models, access information, identify pressures and resilience measures, and set reference points, through in-person meetings, workshops, and remote communication. There are two more techincal requirements:

The toolbox is built upon the programming language R. The technical team member(s) need to be skilled in R Setting regional boundaries and spatial analysis requires access to GIS software (some of this can be done in R).

Sample OHI Team structure

The OHI team can offer in-kind support (scientific, managerial, and communications), but for local technical information and support, you will require dedicated specialists.

3.1 Collaborative Target Setting and Indicator Framework

3.1.1 Setting reference points

As discussed in Phase 1, in the OHI framework each goal has four main components: status, pressures, resilience, and trend. The status of each goal is calculated by comparing the present state of a system against a pre-established target (reference point), which should be used to articulate management guidelines and objectives. Setting reference points for each target is very subjective as this represents the ideal scenario under which a goal would get a score of 100. As a general rule, OHI reference points should meet SMART criteria:

Specific: clearly define what will be accomplished

Measurable: have quantitative and/or qualitative means of verification

Ambitious: capable of changing the status quo

Realistic: capable of being achieved with predetermined resources

Time bound: limited to a specific time scale

Four different categories of reference points are used in OHI:

- Functional relationships: established based on scientific evidence as a relationship between the capacity of the system to provide a benefit relative to the human pressures exerted on that system (ex. Maximum sustainable yield for fisheries)

- Temporal comparisons: a condition or status in the past is used as a target to compare to current status (ex. extent and condition of coastal habitats in the year 1980 compared to present status, or emissions standards as 20% below 1990 levels)

- Spatial comparisons: a condition or status of a specific geography is used as a target to compare the current status of the geography assessed (ex. comparing a high performing state against all others)

- Know targets: those that are established through conventions, laws, regulations, policies, and governance

As you can see from the list above, determining which reference point (target) to use can be tricky and can lead to conflicts between users. If the target is too high, it may not be feasible or realistic, and its costs may outweigh the benefits. If the target is too low, it may not be ambitious enough or improve current situation, which may lead to high socio-ecological costs in the long term. Moreover, any given target by default will have winners and losers. It is possible for a good target to have diffused benefits, but concentrated costs; that is even though it may benefit society at large, it could imply significant loses for particular groups. The inherent subjectivity surrounding the establishment of reference points make it necessary to make this a participatory process, aimed at reaching consensus and agreement among stakeholders in order to minimize potential conflicts in the future. It is important to mention that in many cases it is data availability that determines the feasibility of a specific reference point. For example, stakeholders may want to restore habitats to the way they were back in the 1920s, but if there is no reliable information available about the status of those habitats back then, it is not a feasible target.

Ideally, the SNA process will yield preliminary information about potential reference points for each goal in the OHI framework. Stakeholders should Identify and select qualified resource people to assist the conveners with target selection. This expert group can then narrow down the options to 2 or 3 potential reference points per goal and analyze the merits and consequences of each, taking into consideration feasibility (data availability) as well as potential impacts to specific groups. Even though data availability may limit the feasibility of some potential reference points, it is important that they are discussed, considered, and recorded in decisions documents, as their importance may guide efforts to make them a realistic target in the future.

3.1.2 Identifying information for the indicator framework

In Phase 3 we discuss the process of Discovering and gathering input information from existing sources. However, it is important that you consider the ideal approach for measuring each goal early in the process. Establishing an indicator framework can help you determine what relevant information is needed to adequately inform decision-making. In the OHI framework, each goal uses several indicators to estimate the goal’s status, as well as the associated pressures and resilience. Much like reference points, these indicators should follow SMART criteria. By separating the indicator framework from the existing data discovery, you are able to identify the “ideal” information required for each goal, which you can then cross-check with existing information. Doing this will allow you to identify data and information sources you need but do not have, so you are able to establish protocols for gathering that information. Therefore, in the short-term you are able to work with the readily available information while preparing yourself for using the ideal information in future assessments. In Phase 3, we will introduce you to your OHI virtual repository which you can use then to store and analyze your data.

The availability of local data is perhaps the single most important requirement for conducting an OHI+ assessment. Time-series data are needed for the four components of each goal: Status, Trend, Pressures, and Resilience.

These are the types of data that have been used in previous assessments:

Data required for status and trend:

- Fisheries and mariculture harvest

- Natural products harvest

- Need and ability for small-scale fishing

- Coastal habitats coverage area and condition

- Employment, wages, and revenue of coastal industries

- Species list, extinction risks, and protection of special places

- Tourism and recreation information

- Water pollutants

Data required for pressures:

- Ecological pressures

- Pollution

- Habitat destruction

- Species threats

- Fishing impacts

- Climate change

- Social pressures

- Social pressures

- Governance indicators

Data required for resilience:

- Ecological resilience

- Regulatory framework

- Ecological integrity

- Social resilience

- Social integrity

- Governance indicators (policies, enforcement, effectiveness)

Case study: Colombia’s Ocean Indicator Framework

Colombia was one of the first countries to begin an OHI+ assessment: they have been working for 2.5 years. Their work has already yielded positive policy and management changes. The Colombian Ocean Commission (CCO), in partnership with the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), has created Colombia’s Ocean Indicator Framework, which establishes measurements for 113 components relevant to the management of social, economic and ecological features. In 2016, the CCO and DANE will be partnering with key government agencies, both at national and regional levels, to create methodological sheets for each indicator, a step aimed at establishing consistent protocols for data gathering at the various scales of management. These methodological sheets will indicate the measurement, the frequency of data collection, which agency is responsible for collecting it, and which methodology should be employed. The indicator framework centralizes all of Colombia’s information relevant to ocean management and facilitates the efforts to develop a comprehensive ocean knowledge baseline upon which changes can be compared. This system will make it easier for Colombia to continually update its OHI scores when new information becomes available, simplifying the effort of data gathering, and ensuring assessments are repeated frequently to guarantee decisions are made with the most up to date information. In an effort to align national and regional policies for ocean information management, CCO is also holding regional workshops within the country to build regional capacity in terms of ocean data collection procedures. In creating a standardized system for ocean information management, Colombia is establishing a long lasting building block that will allow them to measure ocean health continuously and inform decision-making, which will result in a better allocation of resources. This accomplishment demonstrates the value of the process rather than solely focusing on OHI scores. Because fostering ocean health involves far more than doing scientific assessments, it is important stakeholders focus on creating the enabling environment that will make scientific information relevant and useful for policy and management.

3.2 Workshop

Following the SNA and the initial target setting and indicator selection exercises, the conveners should host a stakeholder workshop, aimed at discussing the results of the SNA as well as the proposed reference points for each OHI Goal. All people interviewed during the SNA as well as stakeholders identified should be invited and encouraged to participate in this workshop. The workshop provides an opportunity for stakeholders to work together and ensure their interests are captured within the context of the OHI assessment. Further, it is the space where the governance structure will be determined; that is, the format used to make decisions as a group. During this meeting, OHI methodology is explained in more detail to ensure all stakeholders understand the framework and the process. You should also discuss whether all 10 OHI goals are relevant to the local context Lastly, the workshop serves as an initial planning meeting. Here, you should identify potential members for the management and technical teams (or discuss proposed members), as well as develop an initial work plan of next steps to ensure the OHI assessment evolves within a reestablished time line.

The convener and stakeholders must decide together how far they would like to take the OHI process. There are two possible options: 1) work with stakeholders to test management options and reach agreements among them, or 2) simply provide recommendations for management based on the findings. Your decision will largely depend on local conditions, such as stakeholder willingness to continue their commitment to the process and their willingness to engage with each other to implement agreements over the short-to-medium term.

3.2.1 Key workshop considerations

- Develop a locally relevant agenda using the template provided

- Create and distribute (a month prior) a workshop invitation letter

- Ensure consistency among participant levels; recruit high-level/influential participants – need buy-in from the start to signal - seriousness of intent

- Consider private sector participation (likely via associations)

- Determine and disseminate desired workshop outcomes: commitment & work plan

- Identify a good neutral convener with skills & credibility — managing the conversation, independent professional neutral conveners are worth paying for. A good convener has: demonstrated experience and skill in assisting multi-stakeholder groups to reach agreement on complex issues a basic understanding of the substantive issues involved (e.g. rural development, urban informal settlement) impartiality with regard to the interests of the stakeholders involved in the process, and with regard to the specific issues to be discussed and negotiated Examples: University/think tank based people (social sciences) — not marine experts, neutral institutions such as senior retired person from public/private sector (e.g., former minister), academia

- Reportage of stakeholder needs assessment (did we miss anything?)

- Discuss proposed governance structure (does it exist already? is it effective? do we need to create something anew?

- Present proposition (recommendations, proposed workplans, etc.) and leave disagreements open for discussion. Then refine proposition with stakeholder input

- Optional half day for scientific and technical discussions

- Clarify facts & options

- Questions, experts, methods, reports

- What are tradeoffs?

- Experts develop options rather than an answer — and a rationale

- Proposed reference points are discussed with broader stakeholder group

- Option: final decision is discussed with stakeholders (one last round of consultation)

3.3 Establishing Your Strategy: Guidelines for your assessment

Your strategy should be a results-based planning document that details the results and objectives that will be achieved through the assessment and the specific activities, human resources, and funding needed to achieve them. Having an assessment strategy ensures that financial and human resources are used systematically and logically to accomplish the intended objectives.

Those involved in developing the assessment should use a planning approach that is familiar and comfortable to them. All strategies should at a minimum answer these key questions regardless of the exact approach or timeline:

What do we want to achieve by developing an Index assessment?

Who will use the strategy, and for what purposes?

Who will be involved?

What national/local policies, mandates, or initiatives could OHI+ complement?

When will the assessment be completed?

What funding and support are available?

Your strategy document should include key characteristics and priorities before gathering information. This requires an inventory of information and knowledge that spans disciplines, space and time, and can be a useful process for understanding the current policy, information and knowledge landscape. The strategy needs to simultaneously include broad ocean benefits and key characteristics reflecting social values and priorities specific to the context. These will extend beyond any single discipline or knowledge base and should be specified before information gathering begins.

The developed strategy will provide the necessary structure to later identify, process and combine information. Explicitly drafting the strategy for the assessment so that it is in accordance with local priorities and perspectives makes the findings more useful for established needs. Doing this before assembling information is also critical because it can reduce potential bias, since an assessment framework built around the availability of known information may unduly skew the assessment and ultimately produce scores that misrepresent the assessment’s stated purpose.

The assessment planning approach should be appropriate to the local context. It is important to carefully consider the physical, social, political, economic and environmental characteristics of the study area to develop a realistic and achievable plan. The process we recommend in this guide can be followed step by step, but it is better if it is adapted to local needs.

It is important to create a detailed planning timeline, detailing specific deadlines and milestones to help organize and coordinate production.

3.3.1 Key Components of an Assessment Strategic Plan

An effective Strategic Plan includes (but is not limited to) the following key components:

- Purpose of your assessment

- Introduction to the study area, background information, and justification for using OHI

- Alignment of OHI with management needs, as well as existing policies and initiatives

- General and specific objectives

- List of resources needed to accomplish goals and objectives (human, physical, and financial)

- Key stakeholders (refer to Stakeholder Analysis)

- Identify potential constraints

- Timeline of activities

- Communications strategy

- Linkages with decision-making

- Establish accountable and responsible individuals/organizations for each objective/task

3.3.1.1 Creating a Vision: What’s the purpose of the assessment?

Producing the Index is not the end goal: It is merely a process toward the true end goal – achieving improved ocean health.

Index findings can be used by decision-makers to establish ocean health outcomes and management actions that have measurable impacts. Establishing a common vision and determining early in the process how the findings will be used and by whom, makes the final goal clear to the greater community (as well as to stakeholders and participants). Social, political, ecological, economic, and governance criteria should be considered when determining the goal for an assessment.

Establishing a vision is the first step, and will help identify outstanding important issues that may need to be addressed later on. Here, it is important to think about why is there interest in completing an Index assessment. For example:

-

What are the existing stakeholder problems, needs, and interests that need to be addressed? Are there conflicting uses of ocean and coastal resources?

-

Is the objective to use the findings to reform policies and/or improve practices?

-

Are there any specific management priorities established through government mandates, private sector initiatives, and/or international treaty obligations that would especially benefit from an Index assessment?

-

Are there any special management needs?

-

Is there a need for stronger multi sectorial collaboration for effective management?

3.3.1.2 Establishing Objectives

You must first concrete objectives for the assessment process itself: - Engage stakeholders and create Working group - Identify local characteristics, priorities, and determine the goals to assess - Define spatial regions for the assessments - Establish Technical Team that will conduct the assessment - Discover and gather data, indicators, and other information for status, pressures, resilience, and trend for all goals to assess - Develop goal models - Establish sustainable reference points using SMART criteria (as stated in Reference Points in Phase 1). Your reference points should align with management targets established on a predetermined timeline. - Learn and use the OHI+ Toolbox - Establish communications and outreach efforts

Second, create short and long-term objectives highlighting intentions for the findings and iterative activities for future assessments. This refers to specific measurable results for your assessment’s broad goals. The assessment objectives describe how much of what will be accomplished by when. The objectives should describe the future conditions after the problem has been addressed (think of the reference points), following a logical hierarchy, and illustrating their relationships with the final goal. In defining the objectives, you should also describe the intended strategies (the how) to reach the desired objectives. These strategies can range from the broad (stakeholder analysis) to the very specific (institutionalization of the Index).

3.3.1.3 Determining the Spatial Scale

It is important to remember that the scale of your assessment should match the scale of decision-making. Most assessments focus on political boundaries, since most agencies and organizations gather and report data at this spatial scale, however, assessments can be conducted at any spatial scale including transboundary areas and ecoregions.

Index goal scores are calculated at the scale of the reporting unit, which is called a ‘region’ and then combined using a weighted average to produce the score for the overall area assessed, called a ‘study area’.

When deciding the spatial scale of the assessments, the Working Group should consider the following:

At what spatial scale are most data collected?

What are the existing governance or political boundaries that would be relevant? (governance/decision-making boundaries are needed if the Index will be useful for management)

If managers and/or policy makers are interested, what needs to be measured and why? At what scale do they work?

These questions are important to keep the Index assessment relevant but ultimately data availability will be the most important factor when defining boundaries for the Index.

There is no single criterion for identifying the scale of the study area since the Index can potentially be used at all scales using data, parameters, interests, and goals at the scale of the study.

3.3.2 Considerations for Joint Planning

Collaborative assessment planning is an effective approach to ensuring that the assessment will be useful for decision-making. Strengthening scientist-decision maker partnerships creates opportunities for applying research findings to improve ocean health.

-

Create a work plan that has research and management objectives

-

Align research with policy issues to ensure all parties are pursuing the same objectives

-

Share timeline of the study – availability of results, critical decision-making dates (budgets, planning, etc.) – releasing findings strategically can increase impact

-

Identify sources of high quality information and data

-

Plan communications to make the information accessible to stakeholders and various decision-makers

-

Funding strategy should include short and long term planning for science, communication, and action

-

Fundraise with decision-makers: Align research with policy issues to ensure both parties are pursuing the same objectives

-

Articulate the agreed plans in writing (scientists also share a research plan)

-

Create a budget that includes a communications component to cover costs of nationally disseminating findings: providing briefings about findings and applications of if the Index to agencies, decision-makers, and managers who will use the Index

-

Allocate ~15% of the budget to science outreach and communications (eg. travel, time, meeting costs, planning, production of materials)

3.3.2.1 Resources

Tools to help you develop these planning documents can be found at the following sites:

3.4 Funding

Independent assessments can be completed at varying costs depending on the local context. Most assessments up to date have been funded by the public sector. However, in some other cases foundations, research labs and academic institutions, and/or the private sector have provided the funding.

3.5 Costs and Financial Planning

Funds are needed for:

- Human resources (Technical Team)

- Workshops, trainings, meetings, stakeholder engagement, and travel

- Research (data gathering, spatial and statistical analysis, model programming)

- Outreach and communications (including publications) The budget should provide a detailed estimate of all the costs to complete objectives and activities. It might be helpful to separate the budget into the first three Phases of the Index process. The budget should allow the satisfactory completion of all the activities to accomplish the objectives. Given the scientific nature of the Index, engaging qualified human resources may be the highest cost involved in developing an assessment.

Note: it is difficult for us to provide exact figures on the cost of an assessment because the costs vary widely depending on the local context and the scope of the assessment. Past assessments have ranged from ~US$250,000 to US$2 million.

It may take up to eighteen months to complete an assessment, therefore, creating a financing plan is recommended to determine how the expenses in the budget will be covered over time.

It is also important to understand tasks and commitments made under contract, including the disbursement time frame, financial reporting schedule, and possible renewal options. Also consider future finances for long-term objectives.

As the budget is developed, consideration should be given to the source of financing for the assessment. When identifying funding sources, make sure the team understands the tasks needed to secure and maintain any contracts and/or grants awarded. As part of identifying roles and responsibilities in the step above, it will be important to choose a person or group who will be responsible for tracking and monitoring the finance plan (the Working Group could be in charge of this step).

Depending on the local context fundraising can be an important challenge to overcome. Foundations, NGOs, research institutions, and/or the private sector could serve as donors. It might be beneficial to design the financing plan in a “modular” way, so that key pieces can be pulled out from the plan to respond to specific funding opportunities.

The OHI program does not offer funding for assessments. However, Conservation International may be able to support assessment activities through field programs. The OHI program offers significant in kind contribution to those doing assessments: we facilitate trainings and workshops and provide technical, managerial, and communications support. For more information about the OHI program and the team refer to the About Us page.

3.6 Communicating with Key Stakeholders

Once you have identified your key stakeholders, it is important to communicate the OHI+ framework through a lens that will promote buy-in. By referring back to your stakeholder analysis, you can create a strategy for approaching each stakeholder by finding which aspects of the benefits of running an assessment line up with each potential stakeholder’s current efforts or motivations.

Below are examples of language and messaging that can be used to describe the index to various stakeholders:

OHI+ assessments use the same framework as was applied to the global assessments, but allow for exploration of variables influencing ocean health at the smaller scales where policy and management decisions are made. Goal models and targets are created using higher resolution data, indicators, and priorities, which produce scores better reflecting local realities. This enables scientists, managers, policy makers, and the public to better and more holistically understand, track, and communicate the status of local marine ecosystems, and to design strategic management actions to improve overall ocean health.

OHI+ is open-access and free. Results of OHI+ assessments are entirely maintained by the independent groups. Our team supports OHI+ assessments by providing a suite of tools to understand the OHI, and to plan the assessment and carry it out, communicate its results, and help make the study as useful as possible for decision makers.

This approach has been tested at several spatial scales (global, regional, national, subnational) and can be tailored to accommodate different contexts, management priorities, and data quality. The process of conducting an assessment wit the Index can be as valuable as the final calculated scores, since it provides local stakeholders with a consistent framework to combine knowledge, management priorities, and cultural preferences from many different perspectives and disciplines.

OHI+ case studies were completed in Brazil, the U.S. West Coast and Fiji. These first three assessments tested the scalability of the index framework, and were done in a largely academic manner, without large engagement from local managers, and stakeholder. However, managing oceans and coasts holistically requires strong stakeholder involvement in order to achieve desired outcomes and improve ocean health. Currently, our efforts have evolved from conducting OHI+ assessments in an academic fashion to supporting independent in-country groups (such as government agencies and research institutions) as they adapt the Index framework to their own contexts, with a focus on using the findings to help inform management decision-making and track performance through time. Several countries or regions have successfully completed an OHI+ assessment, including Ecuador, Israel, and China, while many more assessments are in progress.

Goal scores are calculated individually for each region in the assessment’s study area. The ten goals are averaged together (equally by default) to form complete Index scores for each region, and then combined by offshore-area-weighted average to produce a single score for ocean health for the entire study area. Goal models and pressures and resilience components are the same for each region; only the underlying input data differ between regions.

In global assessments (Halpern et al. 2012, Halpern et al. 2015), scores are calculated for the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of each coastal nation and territory (two hundred twenty one regions), and then combined by offshore-area-weighted average to produce scores for all EEZs globally (study area). The Index framework has also been adapted for regional assessments at smaller scales, where data and priorities can be at finer resolution and more in line with local management needs and policy priorities.

3.6.1 Using OHI to Support Environmental Peacebuilding

Because the OHI framework integrates multiple goals that interact with one another, the framework lends itself to understand how resource users and stakeholders can work together to prevent conflict and foster sustainable use. This is consistent with the concept of environmental peacebuilding, which “integrates natural resource management in conflict prevention, mitigation, resolution, and recovery to build resilience in regions affected by conflict” (http://environmentalpeacebuilding.org). OHI assessments can help catalyze decision-making across multiple sectors in a way that explicitly evaluates the inherent trade-offs of management actions.

In doing so, stakeholders can better identify the winners and losers of specific courses of action and design interventions that alleviate some of the undesired effects on specific groups or ocean benefits. Environmental peacebuilding is an effective mechanism used to prevent the “tragedy of the commons,” where individuals puruing resource use in their best personal interest, results in the demise of the resource for all users in the long term. Therefore, sustainable natural resource management is far more likely when conflicts between resource users are adequately addressed and minimized.

3.6.2 Adaptive Management

“If the Index were adopted as a management tool, recalculating scores regularly could reveal whether management actions had the intended effect on both overall ocean health and particular goals” (Halpern et al. 2014).

Findings will help inform decision-makers about management actions and policies. However, understanding the effect of management actions requires institutionalizing the tool as a decision-making support mechanism, in which assessments are conducted regularly. Therefore, we strongly recommend you plan on conducting repeated assessments in the future to continuously adapt management strategies. Future assessments may not require as much time or funding as the initial assessment, since the focus is to update data and reference points. For this reason, management plans must include a thorough mechanism to track any changes (i.e. data and indicator collection) related to the assessments activities.

A repeatable process of Index assessments can help determine how well the management interventions are accomplishing the established targets. Through this process, the design, management, and monitoring of the project should be used to continually gather information on the effectiveness of its decision-making process. As information is gathered and assessed, it is possible to recommend policy and management reforms as needed, providing a flexible decision-making process that constantly improves. This will provide key information to decision-makers so they can adapt their management strategies over time, in a way that increasingly moves closer to the target.

Continuous monitoring of the strategy will also help improve resource allocation, so the strategies remain cost-effective.